Indus Script: Patterns

Nisha Yadav in collaboration with others has done important work on pattern analysis which will be of great help to scholars in further deciphering the Indus script.

I want to show you a few examples of Yadav’s work, and expand on them in the light of the Cave Script Translation Project. I have used the patterns to help me decipher some of the Indus Script signs. It is important to stress, however, that each of my translations will need to be checked for consistency against every instance of the signs in the Indus texts.

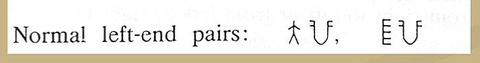

Jars and Baskets

In the illustration above, there are two examples of character pairs that normally appear on the left¹, in other words at the end of the script.

One of the symbols should already be familiar to you. It is the character dà 大, meaning large.

Each of the pairs includes a symbol that resembles the character kǎn 凵, which means container. However, in this instance, the character has some extra lines, in other words it is a composite character.

In Classical Yi, a short line above a longer line [equivalent to the Chinese character èr 二] means two (the numeral), but two lines of equal length means lip². I therefore conclude that Indus Script sign number 342 is a pottery jar.

Hence, the text on the left reads: ‘Large pottery jar’.

From this initial translation it is possible to deduce that signs attached to the generic character kǎn 凵, describe the nature of the container.

It then follows that perhaps Indus Script sign number 347 is a basket. It is a composite of kǎn 凵 and cǎo 艸, meaning plants or grass.

Indus Script sign number 352 is a composite of kǎn 凵, the lip symbol, and cǎo 艸, which gives me a pottery jar in a basket.

Seals

I have not identified the remaining character in the left-end pairs illustration, but following the first example it should be an adjective. From Yadav’s studies, I also know that it sometimes occurs in pairs³; that the orientation can be reversed⁴, and that it can be found in composite characters.

From this I have narrowed the options down to one candidate. I would suggest that Indus Script sign number 176 is a stylised hand, and represents a seal.

I conclude that the second Yadav example reads: ‘Sealed pottery jar’.

It then follows that Indus Script sign number 178 might be the verb to seal; stamp or imprint, which has an equivalent in the Chinese character yìn 印. This symbol incorporates the Chinese character zhuǎ 爪, meaning talon or claw. You should note that zhuǎ 爪 mimics the shape that a hand makes when holding a seal device.

It is also possible to determine some occupations. Indus Script sign number 19 is a person authorised to seal things. One possible translation is clerk. Sign number 20 has an additional mark meaning most senior [my interpretation based upon the modern Chinese character tài 太], so the head clerk. Sign number 38 has the seal around his waist: an official.

Furthermore, the head clerk in Mohenjo-daro appears to have had his own seal (right).

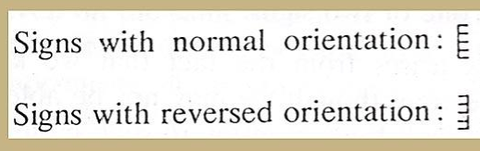

Orientation

Indus Script sign number 176 (the seal) with reversed orientation (below) might mean open, or unsealed, or perhaps unofficial.

Another example of a symbol which sometimes has reversed orientation is the character dāo 刂, meaning knife. The translation will depend upon the context, but the verbs to separate and to join are likely candidates.

One variant of which I am already aware is the verb ‘to unhitch’. According to the Mahadevan Concordance there are 24 examples of this verb in the corpus of Indus inscriptions⁵.

Image: Iravatham Mahadevan: Compilation: Nisha Yadav et al.

Image: Iravatham Mahadevan: Compilation: Lynn Fawcett

Bird Restraints

Going back to the subject of containers for a moment, Indus Script sign number 81 appears to be a pictograph of a bird in a cylinder, in other words a bird restraint. The bird is valuable enough to require protection during transportation. Indus Script sign number 64 gives us an example of such a bird. It is a fishing cormorant, Chinese character jiāo 鵁. In this instance the jiāo 交 might be translated as hand over, which is what the bird does with its catch. Interestingly, a clay tablet from Mohenjo-daro (see below) depicts a boat with what may be two cormorants on the boat, and a third cormorant in the water.

Alcohol

The clue to deciphering Indus Script sign number 336 is that it occurs on 75 occasions with sign number 89. My first instinct was to translate sign number 89 as the numeral three, but why would you always have three of these containers? Sign number 89 also resembles flowing water; a river; or, three gǔn 丨, depicting downward movement. In this instance it means to pour. Hence I get a container of something that you pour, in other words alcohol. Sign numbers 336 and 89 form the composite Chinese character jiǔ 酒.

Sign Number 336 equates to the Chinese character yǒu 酉, meaning a container for alcohol. Xu Shen said that yǒu 酉 could mean to make wine6.

It follows that sign number 34 probably depicts the man who makes the alcohol.

I have found two different examples of the usage of sign number 336 in Indus Script inscriptions (see below). The inscriptions should be read from right to left. It is noteworthy that, in example one, sign number 336 is associated with alcohol storage, whereas when the sign is paired with sign number 89 in example two, it seems to indicate alcohol consumption.

Sign 336: Example Two

Suggested Translation: 'Drinking Companions'.

Note: Sign Number 211 resembles an archaic form of the Chinese Character dīng 丁.

Sign 336: Example One

The consignee for a consignment of goods.

Note: Sign number 244 is a pictograph of an enclosure (the Chinese character wéi 囗) divided into storage bays [my interpretation].

Repetition

Yadav also gives some examples of symbols that are repeated⁷. You should recognise the symbol consisting of nine squares from Lascaux. It is connected with qǔ 曲, the word tune.

The man with a staff is no longer seen as a standalone character, but does exist in composite words such as yōu 攸, which is said to be a pictograph of a man fording a river, and can mean distant or far. I think that traveller would be a good translation for this symbol. Hence I get: ‘Traveller rejoice rejoice’.

Picture Puzzles

There may also be a pattern to the animal motifs. They appear to be picture puzzles. As such, some represent actual characters that can be found in modern Chinese. In other words, they are rebuses. I especially like the ‘Rhinoceros Inn’ motif. The body of the rhinoceros is composed of two studded doors surrounding a space. It equates to the Chinese character jiān 間, meaning rooms. The studded doors imply an element of security. Next to the rhinoceros is a dish. It is the Chinese character mǐn 皿, meaning plate or dish. Who could resist the offer of a safe place to sleep, together with something to eat?

Next, the unicorn motif.

References

Image Credits:

Left-end Pairs, Reversed Seal, and Separate and Join: All images extracted from Sign List of the Indus Script: Iravatham Mahadevan, 1977: The Indus Script: Texts, Concordance and Tables: The Director General Archaeological Survey of India: Source: Nisha Yadav; Mayank Vahia; Iravatham Mahadevan and Hrishikesh Joglekar, 2008a⁸

Jars and Baskets, Seals, Bird Restraints, and Alcohol: All images extracted from Sign List of the Indus Script: Iravatham Mahadevan, 1977: The Indus Script: Texts, Concordance and Tables: The Director General Archaeological Survey of India

Head Clerk: Reference: M-704a: Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions, Vol. 2, p.42: Edited by S. G. M. Shah and Asko Parpola: Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1991: Courtesy: Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan

Cormorant Boat: Moulded clay tablet from Mohenjo-daro (reference MD 602): Harappa website: http://www.harappa.com/indus/24.html: Accessed: 11 November 2014

Traveller Rejoice: Image extracted from Sign List of the Indus Script: Iravatham Mahadevan, 1977: The Indus Script: Texts, Concordance and Tables: The Director General Archaeological Survey of India: Source: Nisha Yadav, M. N. Vahia, I. Mahadevan and H. Joglekar, 2008b: Frequent Sign Combinations of 2, 3 and 4 signs, Table 8: Ender Three-sign Combinations, p.7: Tata Institute of Fundamental Research: Published in: Segmentation of Indus Texts. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics vol XXXVII (1): 53-72: http://a.harappa.com/content/segmentation-indus-texts: Accessed: 30 August 2014

Rhinoceros Inn: A sealing taken from seal device number M-1906 from Mohenjo-daro: Reference M-1906a: Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions, Vol. 3.1, p.75: Edited by Asko Parpola, B.M. Pande and Petteri Koskikallio: Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 2010: Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India

Notes:

1. 4. and 8. Nisha Yadav; Mayank Vahia; Iravatham Mahadevan and Hrishikesh Joglekar, 2008a: Indus Script: Search for Grammar, Direction indicators of the script, Slide 6: Tata Institute of Fundamental Research: Published in: A Statistical Approach for Pattern Search in Indus Writing. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics vol XXXVII (1): 39-52: http://a.harappa.com/content/indus-script-search-grammar: Accessed: 26 August 2014

2. Preliminary Proposal to encode Classical Yi characters: SC2/WG2 N 3288: Unification Procedure, p.11: People’s Republic of China, Bijie University of China, Bijie, Guizhou, 2007: http://std.dkuug.dk/jtc1/sc2/wg2/docs/n3288.pdf: Accessed: 18 September 2014

3. and 7. Nisha Yadav; M. N. Vahia, 2011: Indus Script: A Study of its Sign Design, Doubling and Repetition, p.28: Tata Institute of Fundamental Research: Published in: Scripta, Volume 3, pp. 133-172 by the Hunminjeongeum Society: http://a.harappa.com/sites/g/files/g65461/f/Indus-sign-design.pdf : Accessed: 6 September 2014

5. Iravatham Mahadevan, 1977: Table II: Frequency of Pairwise Combinations, Col. 3, p. 744: The Indus Script: Texts, Concordance and Tables: The Director General Archaeological Survey of India

6. Xu Shen, 121: Radical number 537; Character number 9757: Shuowen Jiezi (Explaining and Analyzing Characters): Source: http://www.shuowenjiezi.com/: Accessed: 13 March 2015

Cave Script

Translation Project

Cave Script

Translation Project